From my very first field experience in my 3rd year ecology class, I was hooked. Since then, I’ve been lucky to travel to some very remote places, and some less so, getting up close and personal with different species. There’s just something about field work that you won’t get from a book or a classroom. It’s taught me to be more observant and think about survival from the organisms’ perspective. I was happy to be invited to write a post about some of my field experiences for Dispatches from the Field, a blog where field biologist can share their stories from the field. This post is also cross posted here.

When I tell people I did my Master’s working with butterflies I get a lot of different reactions. Among fellow biologists or naturalists there is a certain appreciation for a study species even if it may not be their species of choice. However, among the general public it is a different story. Butterflies, are they even animals?

Butterflies are indeed animals and there are a ton of reasons why butterflies make great study organisms. They are relatively easy to catch, handle and mostly easy to observe. Plus, butterflies are relatively short lived, which makes it easy to study them over many generations. Because of this, a number of butterfly populations around the world have been monitored for decades, resulting in work that has made major contributions to our understanding of population dynamics and conservation.

Part of my project was to assess the Eastern Tiger and the Spicebush Swallowtails’ movement relative to forest edges in the fragmented landscape of southern Ontario. Did they move towards the forest edge, avoid it or a bit of both? To learn about this we caught butterflies and released them at different distances from the edge and followed them using a GPS unit to record their movement.

Working on butterflies had a few benefits. They come out when it’s sunny and are active during the day. Swallowtails are some of the largest butterflies in Ontario, so they take longer to warm up. I didn’t expect to see many out before 10 am or after 5 pm. On a typical day, I rolled out of bed around 8:30 am, ate breakfast, and prepared my lunch. Eventually my field assistant would follow, we would pack the car and be on the road at 9:30 am. The main things to pack were butterfly nets, a cooler with ice packs and a towel, many glassine envelopes, a permanent marker, GPS unit, field guides, lots of sunscreen and water.

After arriving at a site, we would walk around with a net, sometimes up and down a road, through fields or along the forest edge looking for swallowtails. People often say to me, ‘I picture you frolicking in the fields catching butterflies’. Clearly, they have never gone butterfly catching before.

Catching butterflies is anything but graceful. In fact, some advice I was given before heading to the field was, ‘if you don’t look silly doing it, you’re not doing it right’. Truer words have never been spoken. Swallowtails are very strong fliers; they can fly high and fast. I couldn’t count the number of times a swallowtail has outflown me or made me run in circles. I have chased after falling leaves, fallen on my face, gotten scrapes and bruises, gone through poison ivy and swarms of deer flies and mosquitos all to get one more sample.

Through many failed attempts, I quickly learned the tricks of the trade. It is much easier to sneak up on swallowtails while they are on a flower feeding on nectar. However if you miss, there is about a 30 second window for you to redeem yourself; otherwise it will likely outfly you. You can also catch them mid-flight or chase after them, but trust me, it is much harder. By mid-field season, my field assistant and I were pro butterfly catchers; sometimes we caught two butterflies in one go and caught well over 600 throughout the season!

Once a butterfly was caught, we would carefully take it out of the net, put it in a glassine envelope and in the cooler. Because butterflies are ectothermic, putting them in a cooler does minimal harm – as long as it’s not too cold!

There are a lot of myths about touching a butterfly’s wings and people always ask how safe it is for the insect. Their wings are covered in a powder-like substance that is actually tiny scales, which gives them their bright colours and patterns. Lepidoptera means ‘scaly wings’. As butterflies age, they lose their scales naturally. Although you don’t want to handle them too much and make them lose their scales faster, holding them by pinching the wings together just behind the head – the strongest part of their wing – is very safe for them.

After a few butterflies were caught, we would bring them to the release site. For each butterfly release, we would take a butterfly from the cooler, sex it and give it a unique ID in case we caught it again.

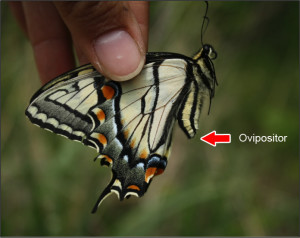

The most reliable way to sex a butterfly is like any other animal: look at their sex organs. It can be difficult at times, but lucky for me, swallowtails are large enough that it makes it easy to tell. Females have an ovipositor at the end of their abdomen that they use to lay eggs and they tend to be thicker bodied. Males have claspers at the end of their abdomen that they use to hold on to the female and they tend to be more slender. Claspers make the abdomen pointed and if you prod at them they will open and close.

To mark butterflies we simply used a permanent marker to write on their wings. For Eastern Tigers, which are mainly yellow, it was easy to write a number on their underwing. But Spicebush butterflies are mainly black, meaning that any number we wrote would not show up against their wings. However, they have six orange spots on their underwings that we marked in unique patterns.

After recording this information, we would put the butterfly on the ground, wait for it to take off, and follow it using flags and a GPS unit, doing our best not to influence its flight. We did this repeatedly throughout the day. When 5pm rolled around and few butterflies were to be found, we headed back to the field station to make dinner, ending the day with a few beers around the campfire.

I have now completed my Master’s and as it turns out, forest edges are an important landscape feature for these swallowtails. It can be stressful to manage your own research project, but when it’s all said and done, I only have fond memories of spend the hot summer days catching butterflies.